Philosophy

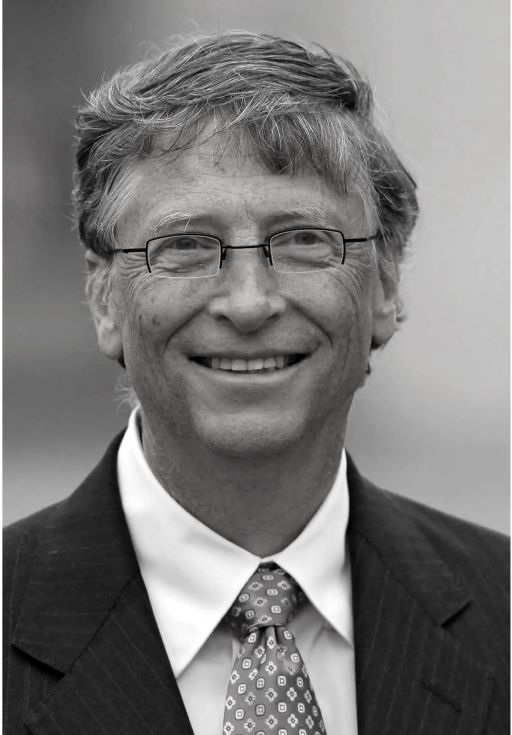

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

1—The Dichotomy of the Mind: System 1 and System 2

Your mind is a constant battleground of two cognitive systems.

System 1, a rapid-fire, intuitive part of our brain, operates constantly, making quick associations and connections.

On the other hand, System 2 is a slow-moving, analytical entity. It's a reluctant beast, only engaged when it's absolutely necessary.

Think of System 1 as your autopilot. For example, reading this sentence or recognizing a friend's face is managed by System 1.

System 2, however, is used for tasks that require focus and deliberation, like solving a complex math problem. Kahneman puts it succinctly:

"System 1 is gullible and biased to believe, System 2 is in charge of doubting and unbelieving."

2—The Trap of Familiarity: Repetition Equals Truth

Repetition is a compelling persuasion tool. If you've heard something repeatedly, System 1 will tell you it's true. Kahneman warns:

"A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth."

3—The Power of Priming

Priming influences your subconscious and shapes your responses.

Kahneman illustrates this with a simple word test. When you read "EAT" and then have to complete "SO_P", you're likely to write "SOUP".

However, if you read "WASH" first, you're prone to write "SOAP". Kahneman notes:

“Disbelief is not an option. The results are not made up, nor are they statistical flukes. You have no choice but to accept that the major conclusions of these studies are true.”

4—The Availability Bias: Readily Available Equals Important

Availability bias skews our judgment based on the information easily accessible to us.

If news about plane crashes dominates the headlines, you might perceive air travel as more dangerous than it truly is. Kahneman observes:

"Nothing in life is as important as you think it is while you are thinking about it."

5—The Art of Substitution: Opting for the Easier Question

Due to System 2’s inherent laziness, we often find ourselves substituting a complex question with a simpler one.

When asked if a certain politician would make a good leader, we might substitute this with the easier question, “Do I like this politician?” Kahneman states:

"A remarkable aspect of your mental life is that you are rarely stumped...The answer to a difficult question is often blatantly obvious."

6—Oversimplifying Stories of the World

We humans are hardwired to seek causes and explanations.

This leads us to concoct simplified narratives about the world, fostering an illusion of predictability and certainty. Kahneman asserts:

"The illusion that we understand the past fosters overconfidence in our ability to predict the future."

7—The Affect Heuristic: Feelings Over Rationality

Our emotional state often controls our reasoning, as demonstrated by the affect heuristic.

Fear, joy, or anger can profoundly shape our thoughts and decisions. Kahneman advises:

"Unless there is an obvious reason to do otherwise, most of us passively accept decision problems as they are framed and therefore rarely have an opportunity to discover the extent to which our preferences are frame-bound rather than reality-bound."

8—Illusions of Skill: The Reliability of Expert Intuition

Real expert intuition thrives on fast and precise feedback. Without it, we're prone to falling into the trap of overconfidence. Kahneman emphasizes:

"The confidence that individuals have in their beliefs depends mostly on the quality of the story they can tell about what they see, even if they see little."

9—Loss Aversion: The Fear of Losing

We're innately loss-averse.

Experiments show that losses hurt us 2-3 times more than comparable gains please us. Kahneman underlines this bias:

"Losses loom larger than gains."

10—The Certainty Effect: The Pursuit of Surety

We are biased towards certainty. We prefer sure outcomes over probabilities, even when the probable outcome might be more beneficial.

Kahneman highlights:

"Most of us view the world as more benign than it really is, our own attributes as more favorable than they truly are, and the goals we adopt as more achievable than they are likely to be."